You’ve probably heard the quote, “Above all, do no harm.” It’s an adage we physicians are taught from day one. We learn that every medical intervention has benefits and risks, and assessing that risk/benefit relationship is a critical part of helping patients achieve and maintain their health.

In the medical community, we primarily weigh the balance between benefits and risk using the measuring stick of “number needed to treat” (NNT), as well as “number needed to harm” (NNH).

This metric is useful for you to consider, too, because while your doctor makes treatment recommendations, the decision is ultimately yours. When you’re deciding whether to take a medication, for example, you need to consider the advantages and disadvantages of treatment options. Knowing about NNT can help you assess potential risks, including side effects and drug interactions.

Let’s further define number needed to treat (and number needed to harm) to help you navigate the systems that are, undoubtedly, trying to sell you something.

What Is Number Needed to Treat (NNT)?

Number needed to treat (NNT) refers to results of pharmaceutical clinical trials. It can be a convoluted topic to discuss, so I’m going to use the most straightforward laymen’s terms. Wikipedia’s definition of NNT takes a concise approach: NNT is the average number of patients who need to be treated to prevent one additional bad outcome.

For example, in a clinical trial, how many patients need to be treated for one of them to benefit when compared with a control group? That number is the number needed to treat.

NNT is reported as a number, and the lower the number, the better.

Let’s take the following example: If a drug has an NNT of 10, it would take 10 people treated with the drug to observe one case of benefit or avoidance of one bad outcome. In other words, an NNT of 10 means one in ten people sees a benefit from that drug. That’s far less compelling than an NNT of one, which means the benefit is present in all people who are treated.

If you’re looking for a drug with a high benefit, you want an intervention with a low NNT.

Hand-in-hand with number needed to treat is number needed to harm (NNH). NNH represents the average number of patients who need to be exposed to a risk factor from a particular drug before harm is caused.

Let’s imagine a drug we’re studying has an adverse effect of causing blood clots. NNH reflects the number of people who didn’t develop blood clots during the clinical trial. Very simply, the lower the NNH, the more risk or harm.

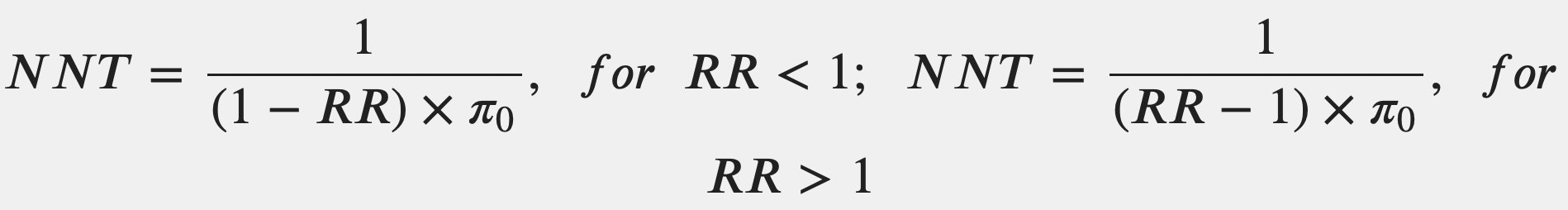

The formulas that determine NNT and NNH are complicated. Just to give you an idea, here’s an example of one from the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

But you don’t need to master a formula to use NNT and NNH as a meaningful indicator. The bottom line is, NNT and NNH vary widely, and could cause serious issues if someone is taking a drug unnecessarily.

Why Should You Know About Number Needed to Treat?

There’s a powerful force we can fall prey to when we don’t know about NNT: marketing.

We are exposed to incalculable amounts of marketing — while watching the evening news or our favorite sports team; while listening to a podcast or a playlist on a run or while cooking dinner. It’s ubiquitous; it’s insidious — and often, it’s very slickly done.

Ads for medications are cunning; they target us on every level they can — universally appealing visual cues, music that engages us while they list the adverse effects, just the right language — while speaking to our pain points. These carefully crafted ads exist to make people talk to their doctors about that medication. And they do!

This is a place where I believe a physician needs to pay close attention. Too often the physician will write an unnecessary prescription because it enables them to move on to the next patient. There’s even a term for this in the medical community: the trophy. If a patient comes looking for a prescription, it’s considered easier to give them one so they feel like they got something worthwhile. “Let them leave with a trophy!”

The truth is, it’s much more difficult and time-consuming for a doctor to explain why we shouldn’t do something than it is to just do the thing. In fact, the hardest thing is to do nothing and to reassure, but sometimes that’s the best way to do no harm.

Patients Deserve Individualized Care

This may seem obvious, but patients are individuals. They respond individually to diseases and to treatments. Every treatment has not only a risk of harm, but also a risk of cost and inconvenience.

When a doctor takes the time to have an actual back-and-forth conversation with a patient, the two individuals can become a team, deciding the best course of action. Indicators like number needed to treat and number needed to harm give physicians and patients information that can clarify how beneficial — or harmful — a particular pharmaceutical actually is.

These are the kinds of measurements that can help us discern the right course for health — not the filtered glow of a warm camera shot.

Dr. David Rosenberg

Dr. Rosenberg is a board-certified Family Physician. He received his medical degree from the University of Miami in 1988 and completed his residency in Family Medicine at The Washington Hospital in Washington, Pennsylvania in 1991. After practicing Emergency Medicine at Palm Beach Gardens Medical Center for two years, he started private practice in Jupiter, in 1993. He is an avid baseball fan and Beatles fanatic, since he was 8 years old. He has been married to his wife, Mary, since 1985 and has three grown children.

David completed additional studies at Mercer University, Macon, Georgia and obtained a BS in Chemistry in 1983.

“My interests include tennis, snow skiing, Pilates and self-development.”

Subscribe to our Newsletter!

Receive latest blog posts, health tips, and exclusive offers from Jupiter Concierge Family Practice straight to your inbox.